The Ta Prohm temple is a temple that has been heavily overgrown with trees. It stands in what is now modern day Cambodia. However, it was built during the Khmer Empire period, which ran from the 9th through the 15th centuries (Carter et al. 492). This temple, as well as many others, were built by Angkorian kings (Carter et al. 492). Research that has been done on this region shows a very complex water management network as well as architectural features that were inspired by Indic cosmology (Carter et al. 492).

This temple, and many others, are some of the only things that survived from the period, and can help us discover more about the Khmer Empire (Preston 2000). Angkor is littered with temples, including the Bakong temple, Ban-teai Srei and Ta Keo (Daniels, Hyslop and Brinkley 2014). This is because during the Khmer Empire, rulers including Indravarman I, Rajendravarman II, Jayavarman V as well as many more, expanded Angkor by building these vast temples (Daniels, Hyslop and Brinkley 2014). The Ta Prohm temple, built in 1186 CE by Jayavarman VII is one of the these temples. (Lakshmipriya 1491).

To understand the importance of the Ta Prohm Temple, it is important to look at the Khmer Empire and the temple’s relevance in this empire. The empire was founded in 802 CE by Jayavarman II (Haywood 2001). The capital city, Angkor, was established by Yasovarman I. The empire was able to control all of modern day Cambodia under the rule of Suryavarman I and Suryavarman II (Haywood 2001). It later declined in the 15th century and the capital moved to Caturmukha where it became a minor regional power (Haywood 2001).

The Ta Prohm temple is considered one of the most significant temples within Angkor. What is so fascinating about this temple is that it has almost been swallowed whole by trees. It was built as a flat temple, contrasting the “temple mountains” that have often been built in this region (Carter et. al 495). The temple is made out of grey to yellow-is brown sandstones (Uchida et. al 221). Inside the Inner Enclosure of the temple is the Central Tower, the Inner Gate Towers, the Inner Gallery and ponds (Uchida et. al 225). There is an Outer Gallery and with two small galleries connected to it (Uchida et. al 225). Distributed between the Middle Gallery and Outer Gallery are many small towers (Uchida et. al 225). The temple also has a Dancing Hall and House of Fire (Uchida et. al 225). It was an active monastery that was used for Buddhist teaching and learning (Carter et. al 492). An inscription found at the Ta Prohm Temple illustrates in detail the organization and the functioning of the temple. It shows those who worked at the temple and possibly even lived there. This discovery as well as the temple itself is very important as most Angkorian establishments were built out of perishable materials such as wood and grass, so this stone temple is able to tell researchers more about the Khmer empire through archaeological investigation (Carter et. al 492).

As stated earlier, the construction of these stone temples was a key part of the Angkorian rulers’ building strategy. This is how the rulers could establish their authority – by building these elaborate temples. The temples were dedicated to Hindu and Buddhist deities. They were centres for religious practices and brought the rural populations into the city for festivals (Carter et. al 494-95). These temples were also used as universities centred on religious studies and helped the Angkorian economy through receiving temple donations (Carter et. al 495).

King Jayavarman VII (who built the Ta Prohm temple) was one of Angkor’s most famous rulers. The temple was dedicated to his mother and she was represented as the Buddhist deity Prajnaparamita (Carter et. al 495). Prajnaparamita is the main deity in the central shrine of the temple (Lakshmipriya 1493). In Sanskrit, Prajnaparamita translates to “Perfection of Wisdom”. This deity is the personification of literature or wisdom. She is also sometimes referred to as the Mother of All Buddhas. This deity is fitting for the Ta Prohm temple as it was dedicated to King Jayavarman VII’s mother. The temple was given the name Rajavihara which means “royal monastery”. Most stone temples in this region are called “temple mountains” as they are built in a pyramid style like a mountain. This makes the Ta Prohm temple distinctive as it was built more flat (Carter et. al 495). The temple reflects characteristics of Mahayana Buddhism which were relevant during the time it was built (Lakshmipriya 1493). There are numerous shrines and pavilions. It also has images of the Bodhisattva carved into the walls (Lakshmipriya 1493). This emphasizes the prominent belief in Buddhism during the time the Ta Prohm temple was built and used.

What makes the Ta Prohm temple more notable than other temples are the inscriptions found inside it. From these inscriptions researchers are able to understand Angkorian culture in more detail by understanding how they used the temple and who used the temple. The inscription reveal that there were 79,365 people who serviced the temple (Carter et. al 495). There was 18 high priests, 2740 officials, 2232 assistants and 615 dancers (Carter et. al 495). There were also 1409 students who used the temple as a university for religious practice (Carter et. al 495). Some of these individuals also lived in the temple and were from a variety of ethnicities including Khmer, Burmese, and Cham (Carter et. al 495). Other items were also found in the temple including bedspreads, cushions and mosquito nets (Carter et. al 495). All of this information allows researchers to understand this culture better, especially in the sense that the temples were used as more than just a place for religious practices.

The Ta Prohm temple seemed to be of much importance to the Angkorian culture, so what caused it to become so heavily overgrown with trees and almost completely abandoned? The fall of Angkor happened gradually starting with unhappy workers not wanting to help with the demands of its labour intensive economy (Warner 1990). The fall was also impacted by wars with neighbouring kingdoms (Warner 1990). The Thais were able to take full control of Angkor in the early 1400’s which would ultimately end the Khmer Empire (Warner 1990). Thereafter, Outsiders rarely visited Angkor, so these stone monuments were not known to the western world until Henri Mouhot, a French naturalist-explorer, discovered it and published an article about it in 1863. He said that the farmers who worked near by were unsure of who built Angkor. They thought it was possibly the gods or giants (Warner 1990). As the locals are unsure of how Angkor was built this shows even more how important the Ta Prohm Temple is as it shows researchers the culture of Angkor more than locals can even tell them.

Cambodia has been under very harsh times in recent years. The Vietnamese invaded Cambodia and took occupation over it in 1979. However, the Vietnamese doing this were able to put an end to the rule by the Khmer Rouge, during which almost two million people died (Warner 1990). The country is still trying to recover from this painful and destructive time. This means the Cambodian government must focus more on re-establishing its country with basic services before it can focus on restoring any of its monuments such as the Ta Prohm temple (Warner 1990). Not only are these temples in need of restoration, they are still facing numerous environmental threats today that need to be stopped in order to preserve these precious monuments.

The climate in the Angkor region is very seasonal. It receives 1400-2000 mm of rain falling within the summer period between May and October (Hall, Penny and Hamilton, 154). This much rain can cause the Ta Prohm temple to flood up to 1 m some days during this season (Lakshmipriya 1491). This flooding serves as a major threat to the temple and action is required to ensure the restoration and conservation of it. However, the flooding is not the only threat. The temple is also facing challenges against structural stability that has occurred due to vegetation, human vandalism, weathering and foundation movement. There is also decay that has been caused by neglect and lack of maintenance (Lakshmipriya 1493).

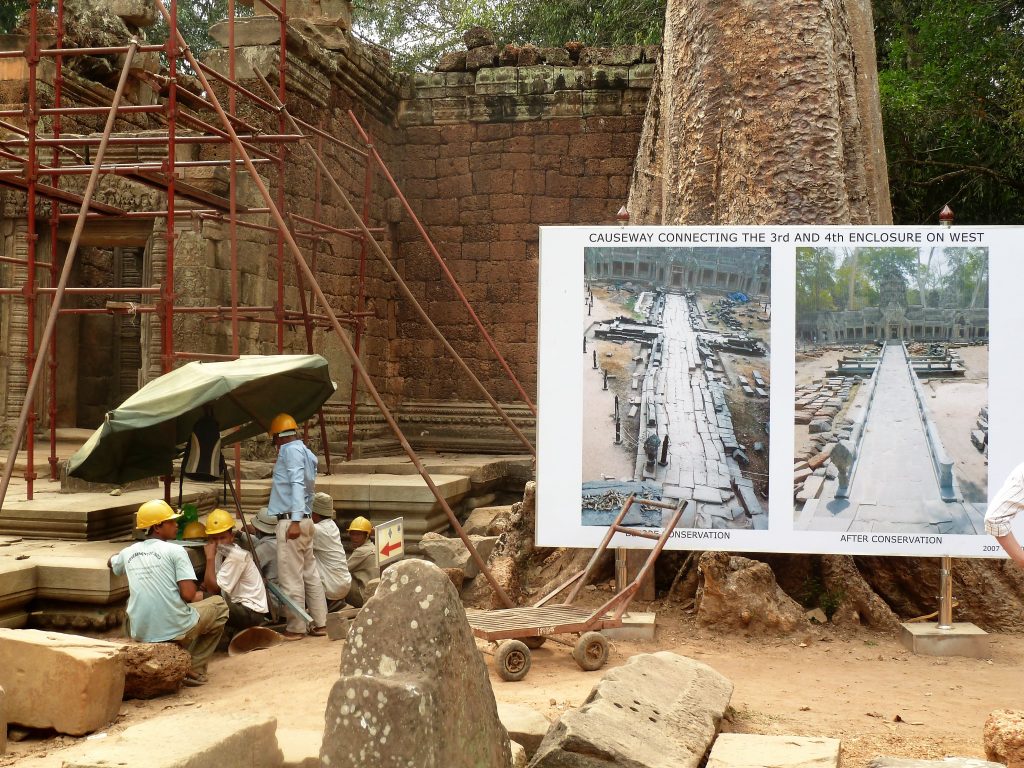

The Archaeological Survey of India has taken the responsibility to take action and conserve and restore the Ta Prohm temple (Lakshmipriya 1491). They have come up with an approach that is meant to help to restore the built heritage of the temple but also conserve its

natural heritage of it (Lakshmipriya 1493). The temple is now commonly known as the “tree temple” since trees have grown in it and around it. This means when preserving the temple they will want to take precautions in ensuring that the natural state the temple has come to be in, is not ruined.

The main guidelines that have been set out to ensure that the temple is not at risk during the restoration is that the interventions will be minimum. Any intervention that takes place must be in consultation with ICC and APSARA Authority. No historical evidence will be damaged during the process. As well as all of the interventions that do take place must be done by experienced archaeological conservation professionals (Lakshmipriya 1494). These are not all the guidelines that have been placed but are the main ones that will help to restore the temple in a safe manner. Through this process the Archaeological Survey of India will hopefully be able to restore the Ta Prohm temple and help to keep it conserved for the next coming years.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER RECOMMENDED READING

Carter, Alison; Heng, Piphal; Stark, Miriam; Chhay, Rachna and Evans, Damian (2018) “Urbanism and Residential Patterning in Angkor.” Journal of Field Archeology 43:492-506. Accessed January 28, 2020. doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2018.1503034.

Daniels S. Patricia, Hyslop G. Stephen, Brinkley Douglas (2014) “Khmer Empire 600-1150” National Geographic Almanac of World History. Accessed February 20, 2020.

E. Uchida, O. Cunin, I. Shimoda, C. Suda, T. Nakagawa (2003) “The Construction Process of the Angkor Monuments Elucidated by the Magnetic Susceptibility of Sandstone” Archaeometry 45:221-232. Accessed March 27, 2020. doi-org.ezproxy.uleth.ca/10.1111/1475-4754.00105

Hall, Tegan; Penny, Dan and Hamilton, Rebecca (2019) “The environmental context of a city in decline: The vegetation history of a Khmer peripheral settlement during the Angkor period.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24:152-165. Accessed January 28, 2020. doi-org.ezproxy.uleth.ca/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.01.006.

Haywood, John (2001) “Khmer Empire” Andromeda Encyclopedic Dictionary of World History. Accessed February 20, 2020.

Lakshmipriya, T. (2008) “Conservation and restoration of Ta Prohm temple.” Structural Analysis of Historic Construction: Preserving Safety and Significance 1491-97. Accessed January 28, 2020. doi.org/10.1201/9781439828229.ch174.

Preston, Douglas (2009) “The temples of Angkor still under attack.” National Geographic 198:82+. Accessed January 28, 2020.

Warner, Roger (1990) “After centuries of neglect, Angkor’s temples need more than a face-lift.” Smithsonian 21:36+. Accessed January 28, 2020.

Related Topics for Further Investigation

Angkor Wat

Khmer Empire

Angkor

Prajnaparamita Bakong temple

Ban-teai Srei

Ta Keo

Noteworthy Websites Related to the Topic

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/cambodia/attractions/ta-prohm/a/poi-sig/500632/355852

https://www.amusingplanet.com/2011/05/giant-trees-at-cambodian-temple-of-ta.html

http://www.ancientpages.com/2018/09/03/unsolved-archaeological-mystery-of-ta-prohm-temple- cambodia/

Article written by: Norah Elliott (February 2020) who is solely responsible for its content.